Leaderboard

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation on 07/04/22 in all areas

-

what have people got against a large utility room? having lived in a mass built new-build with a pokey corridor type of utility room where you can't walk past if a cupboard door is open I would (and we have!) go for a large utility room. I see no issues with it if you have the space to do so.3 points

-

I hope this update will be of interest? We have finished the build but for some small details 😃. I bought a modern stove from Kratki , it will wait for winter before connection , it is 35 C here ! I have 2x A/C units fitted so am working in a comfortable 25 C . I have installed a full off grid PV system which is running the A/ C and there is still a surplus of energy 😁 . In fact the growatt inverters shut down occasionally as we are not using enough of our generated power , (open to suggestions here ) The build was challenging for the locals ,who know not the world of Passiv Haus , but we have ticked most of the boxes . It took exactly 1 year to build , on a Greek island , so much more of a challenge especially during the covid situation. The house retains the cool temp overnight , it's a pleasure to walk in at 0800!2 points

-

We have 110mm pipe coming up through the floor under the sink. Think a rubber adaptor seals the 40mm sink and dishwasher waste pipe to the 110mm. Never had a problem.2 points

-

My painter does UPVC to look like wood with a special paint, yes I know it sounds crap but he showed me a sample and it looks really good even close up, grain and all.1 point

-

I’ve used Impey over the last few years Never any issues Probably the stickiest membrane I’ve used1 point

-

Xps high density foam, or get a sheet of marmot board and cut up, or buy the shulter curb.1 point

-

On second thoughts (the cost of those 50/80 litre cylinders in the UK) then subject to distances what @Nickfromwalesdescribes with a buried DHW recirc loop from the main house that isn't recirculated unless the room is occupied would make more sense. You're buying the power cable and cold water feed anyway so you might as well bung a pair of pipes with closed cell insulation on them in a duct in the same hole. Provided that the usage truly will be intermittent that is. I wouldn't plumb in an unvented cylinder on a "temporary" basis though. Lots of faff if you're paying somebody else to do that. I'd chuck in a cheap electric shower instead even if it's just for handwash / dishwash / toolwash use. In ongoing operation you PV > Heatpump > Cylinder in house > Undergound pipe OR PV > Minisplit. If it's a long way from this outbuilding to the house then I'd still chuck in an 80 litre wall hung cylinder. https://www.waterheater.shop/en/products/electricwaterheaters/80-liter/eldom-spectra-80-liter-boiler-manual-control/ https://www.modernheat.co.uk/product/80-litre-tesy-bi-light-electric-hot-water-cylinder/ If you were a European / American you'd rely on the safety valve to discharge a bit of cold water as the tank heated up instead of installing an expansion vessel to take up that water. Not legal in the UK but...for a shed on a building site... 😇1 point

-

AFAIK there is no mention here about the WBS providing DHW. It would be a hugely complex installation for an annex, and require a lot of components / plumbing / header tanks etc. Ahh I was going on this comment in the OP: Eventual use will require hot water - preferably instantaneous, as it will be used occasionally and often for shortish periods . Heat from the log burner in the craft workshop will be sufficient. I thought that was saying Heat energy from the WBS would be sufficient to supply the DHW. Now I see that second sentence is probably about space heating and nothing to do with DHW? If so, great. That matches what I was driving towards too. yes, 12kW PV + battery plus an instance water heater sized appropriately for whatever it is delivering to. (Shower? utility sink? hand basin?). A cylinder is not a good choice for something only used occasionally1 point

-

At present I am thinking of using the Schluter system, they do a kerb, then I was going to do it the old fashioned way and use a dry pack mortar to make the base, then Schluter membrane and joint tapes etc. That is the plan for now, we will see how that pans out once others comment on options and experiences.1 point

-

Use 50mm waste, solvent weld, include rodding points. Plenty of brackets, then you have a solid, larger bore pipe which will handle most waste and if needs rodded its bigger and a solid install. I have a fair bit of inaccessible 50mm waste but access points and a solid install mean I can get in and snake it easily enough. Under my sink I have a 50mm tee, into that tee I reduce to 40 and catch both wastes separately (this gives overflow protection if one U bend blocks and lets you get the job done before you get round to unblocking it). I also use Tee's here and there with a 50mm screw on access point so I can get in.1 point

-

1 point

-

How apt, this weeks comic cover story was all about adding years to your life by putting things in your mouth. A longevity diet that hacks cell ageing could add years to your life A new diet based on research into the body's ageing process suggests you can increase your life expectancy by up to 20 years by changing what, when and how much you eat HEALTH 28 June 2022 By Graham Lawton Brett Ryder I HAVE seen my future and it is full of beans, both literally and metaphorically. As well as upping my bean count, there will be a lot of vegetables, no meat, long periods of hunger and hardly any alcohol. But in return for this dietary discipline, my future will also be significantly longer and sprightlier. I am 52 and, on my current diet, can expect to live another 29 years. But if I change now, I could gain an extra decade and live in good health into my 90s. This “longevity diet” isn’t just the latest fad, it is the product of more than a human lifespan of scientific research. And it isn’t merely designed to prevent illness, but to actually slow down the ageing process – that’s the claim, anyway. Of course, it is a no-brainer to say that our diets can alter our lifespans. Worldwide, millions of people still die prematurely every year from lack of calories and nutrients. Meanwhile, an estimated 11 million die each year from too many calories and the wrong sort of nutrients. Scoffing more than we need inevitably leads to obesity and its pall-bearers, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and cancer. Typical Western diets are also high in sugars, refined starches and saturated fats and low in wholefoods, which add insult to injury by disrupting metabolism. That includes the excessive release of insulin, the hormone that keeps blood sugar levels under control and has a direct impact on ageing. Suffice to say that Western diets don’t push the longevity lever in the right direction. But is it really possible to eat oneself into a later grave? In the US, between 1970 and 2009, average daily calorie intake rose by 20 per cent, to 2520 kilocalories. Other Western countries have followed that trend. The shocking extent to which our obesogenic, disease-promoting and pro-ageing diets are shortening our lives was revealed in recent work from the University of Bergen in Norway. Researchers led by Lars Fadnes modelled what would happen to people who switched from a typical Western diet to their optimal one containing more wholegrains, fruits, vegetables, nuts, legumes and fish and less meat, dairy, refined grains and sugary drinks. Based on data from a huge research project called the Global Burden of Disease study, which, among other things, analysed diets and diet-related illnesses across 195 countries, they found that Westerners could typically buy themselves a lot more time. An optimal diet would include more vegetables than most people eat Westend61 GmbH / Alamy Stock Photo Switching to this optimal diet at age 20 and sticking to it would extend average life expectancy by more than 10 years for women and 13 years for men. And it is never too late: 60-year-olds shifting to this diet would gain eight years of life expectancy and 80-year-olds an extra 3.4 years. Even a diet that is a halfway house between a typical Western one and the team’s optimal one would add six to seven years if adopted at age 20. These surprisingly large responses are probably because the diet immediately improves metabolic health, says Fadnes. “We haven’t gone into the mechanisms, but our hypothesis is that the longevity expectations are linked to reduction in cardiovascular disease and, to some degree, reduction in the risk of cancer,” he says. In other words, a healthy diet can prevent diseases linked to a bad diet. Who knew? However, for decades, many researchers have believed we can do even better, by hacking our biology to actually slow the ageing process. The first inklings came over a century ago. In 1917, researchers at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station in New Haven discovered that female rats that had been starved as pups subsequently stayed fertile longer than average and lived to a ripe old age. Further experiments confirmed that this “caloric restriction without malnutrition” – achieved by cutting calories by up to 60 per cent while supplementing the diet with vitamins and minerals – kept mice and rats healthy and alive for longer. The earlier it was started and the more stringently it was applied, the greater the gain. Caloric restriction has since been shown to be capable of extending healthspan and lifespan in every organism it has been foisted on, including yeast, flies, worms and primates. The results vary widely, but some of the gains in lifespan are spectacular. Mice on caloric restriction, for example, can live up to 50 per cent longer than average – which would translate to about 120 years if replicated in humans. But can it be replicated in humans? Unfortunately, doing human caloric-restriction experiments is extremely difficult. Not only do people find it very hard to halve their energy intake for more than a few days at a time, but the experiment would also have to run for many years to assess whether it had any life-extending effect. “In people, we don’t even really know that caloric restriction has long-term significant health benefit,” says Matt Kaeberlein at the University of Washington in Seattle. And we do know that it can seriously damage the health of people who limit their caloric intake as a result of eating disorders. It is important to note that no one should restrict their diet to the extent that it damages their health. Nevertheless, there are reasons to believe that caloric restriction would extend lifespan in people. One is basic biology. It turns out that, regardless of species, the mechanism by which caloric restriction exerts its life-extending effects is essentially the same: a network of metabolic pathways that assess the availability of nutrients and respond by toggling cells between two biological states, feast and famine. When nutrients are plentiful, these pathways stimulate cells to grow and divide. When they are scarce, cells are told to hunker down and await better days. “We see most organisms going into a maintenance mode and not ageing very much,” says Valter Longo at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. Crucially, part of that process is to sweep up intracellular debris, such as damaged molecules and organelles, to burn as fuel, a bit like throwing bits of broken furniture onto the fire. This detritus is a direct cause of the cellular damage that results in ageing, so destroying it – a process called autophagy – prevents such damage from occurring. Starvation also boosts repair processes, which can reverse damage that has already been done. Feast or famine One key player in this nutrient-sensing system is the insulin receptor. When insulin is released in response to a spike in blood glucose, this cell-membrane protein switches on and helps turn the system to growth and reproduction. It does this in part by activating another nutrient sensor called mTOR, which is the linchpin of the feast-famine system and is of intense interest in anti-ageing circles. When mTOR is on, autophagy and repair switch off. So if glucose is constantly flooding into the bloodstream, the insulin receptor gets stuck in the “on” position and mTOR is chronically activated. Animals subjected to caloric restriction show increased sensitivity to insulin, along with improved liver function and loss of weight and body fat. All these biological indicators were also seen during a rare human trial called CALERIE (Comprehensive Assessment of Long-Term Effects of Reducing Intake of Energy) in which people consumed 25 per cent fewer calories for up to two years. This is another reason for optimism about human caloric restriction, but it still doesn’t get around the fact that the regime is very hard to stick with. However, there is some evidence that less-onerous diets have similar effects – at least in mice. Many involve restricting calories some of the time, such as periodic fasting, which entails eating next to nothing for two days each week, or every other day, or for up to four consecutive days a month. Another is time-restricted eating, such as the 16:8 diet, when all the day’s calories are consumed in an 8-hour window bookended by 16-hour fasts. Both these types of diet are sometimes called intermittent fasting. A third approach is the fasting-mimicking diet in which, for a period of five days a month, individuals eat a plant-based meal plan low in sugar, carbs and calories but high in fat that is designed to evoke the fasting response without total abstinence. (Longo holds patents related to fasting-mimicking diets and has equity in a company that sells them.) If we can tap into the body’s anti-ageing pathways, we can increase healthspan as well as lifespan Thomas Barwick/getty images Other diets that promote longevity in rodents don’t even require fasting, but these are more complicated to follow. Protein restriction, for example, is based on reducing the calories obtained from protein from the normal 10 to 15 per cent to around 5 per cent, with the calories replaced by carbohydrates. More elaborate still is amino-acid restriction, which limits consumption of some of the building blocks of proteins. The main target is ethionine, found mostly in animal proteins, with cuts of 80 per cent or more required. Another is tryptophan – sources include milk, chicken and oily fish – which must be reduced by about 40 per cent. Cutting branched-chain amino acids such as leucine, isoleucine, and valine – mostly found in meat, dairy and cereal – by two-thirds also works. These restrictions appear to exert their effect through mTOR, though exactly why the body responds in that way isn’t clear. Such interventions are generally less effective than full-on caloric restriction. Protein restriction, for example, extends mouse lifespans by about 15 per cent compared with 50 per cent, while time-restricted feeding gives about a 10 per cent boost. But the fact that they are easier has led to claims that they can be directly applied to humans. The past few years has seen a torrent of questionable anti-ageing diets based on this research, says Kaeberlein. “When people start recommending these dietary interventions to the general public, they’re doing so in the absence of any real data suggesting that it’s beneficial, beyond the benefits you get from not being overweight.” Now, however, such claims are finding their way into the scientific literature. In April, the prestigious journal Cell published a review paper containing a “longevity diet… to optimize lifespan and healthspan in humans”. The authors – Longo and Rozalyn Anderson at the University of Wisconsin-Madison – blended decades of research on the biology of ageing, the effects of caloric restriction and similar dietary interventions, and knowledge on the health benefits of various food groups, including from the recent University of Bergen study. Then, they seasoned it with data on the dietary habits of people living in longevity hotspots such as Okinawa in Japan and Sardinia in Italy. The end product is a diet that could add years to a typical person’s life. “It’s going to be associated with a huge effect,” says Longo. “You’re starting to get into 15 to 20-year changes in life expectancy.” The main ingredients of this longevity diet – which is yet to be tested in trials – are enough caloric restriction to stay slim, a daily regime of very mild, time-restricted feeding, a few five-day cycles of fasting-mimicking each year and a largely plant-based diet (see “The longevity diet“). This, says Longo, delivers both a conventional healthy diet that guards against obesity and its consequences, and also taps into the longevity-enhancing starvation response. “This is what we know works, based on epidemiology, clinical trials, basic research and centenarian studies,” he says. Hold on a minute, says Kaeberlein: even in mice, the evidence for the benefits of time-restricted feeding is slender. “There have been a few studies, but they’re almost all short-term – usually eight to 12 weeks – where people claim to see benefits in some cases, and in other cases no benefits. I’d say the body of work is unconvincing.” And it is a similar story with the fasting-mimicking diet. This is essentially a period of caloric restriction and, despite a widespread view that such restriction invariably works, that is a myth. Only about half the strains of lab mouse it has been tried on have the “correct” response, some don’t respond at all and about a third live shorter, not longer, lives. “We don’t really understand why that is,” says Kaeberlein, “It’s a little bit risky to start recommending these things to the general public when even in mice, a third of the time, it actually reduces lifespan and increases mortality.” On top of that, most people who attempt caloric restriction also experience unpleasant side effects, including disturbed thermoregulation, loss of libido and increased susceptibility to infection. Longo is dismissive of these warnings. “The idea is to keep it very, very safe,” he says. He could have recommended something much more hardcore, with caloric restriction, 16 hours of daily fasting and a monthly bout of the fasting-mimicking diet, but deemed it too risky. “Could it help? Yes. But could it hurt? Yes, it could too. So we don’t go there.” The proof of the pudding, of course, will be in the eating. Longo has just secured funding to do an 18-month clinical trial in Italy. He will recruit 500 people and put half of them on the longevity diet, leaving the rest on their normal chow, then track biomarkers of improved health and longevity. He doesn’t have any doubts it will be safe and effective. In fact, he follows the diet himself and has done for 30 years. But while we wait for those results, it is never too late to start living, so pass the beans. Always consult your doctor before radically changing your diet The longevity diet Research published in April identifies six steps designed to increase lifespan by promoting lean body mass and healthy blood sugar levels, switching off the body’s central pro-ageing system and ramping up an anti-ageing process called autophagy: 1 Limit calorie intake to maintain a body mass index of 22 to 23 for men and 21 to 22 for women. 2 Eat a diet high in wholegrains, legumes and nuts. Stop eating meat to restrict intake of the amino acid methionine, but include some fish. 3 Aim to get between 45 and 60 per cent of calories from non-refined complex carbohydrates, 10 to 15 per cent from plant-based proteins and 25 to 35 per cent from plant-based fats. 4 Do a limited daily fast, eating no calories from around 3 hours before bedtime and for the next 11 to 12 hours. 5 Every two to three months, undertake five days of a fasting-mimicking diet (see main story). 6 Alcohol is allowed in small amounts, but no more than 5 units a week.1 point

-

Why haven’t you just drilled straight out and lost an unnecessary additional bend? Then you make the external bend a T with a cleaning ( rodding ) eye on the end for self maintenance.1 point

-

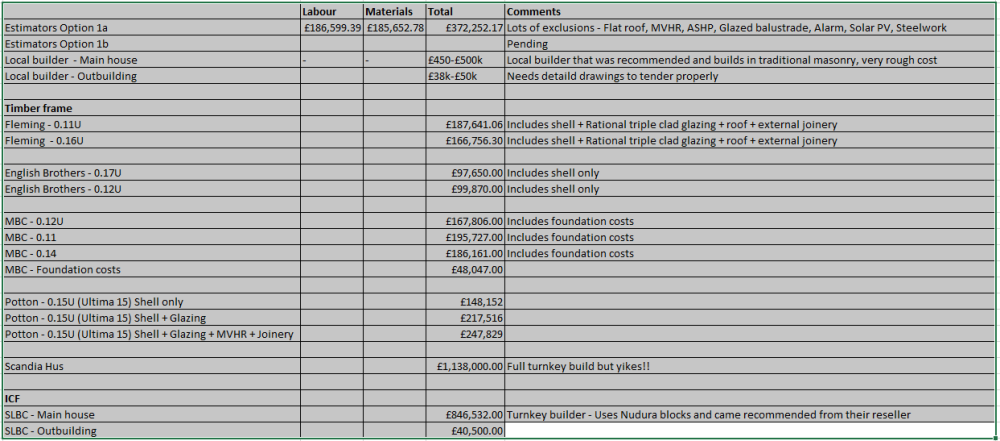

Coming back to this thread after a long time, but I thought it's easier to do it here rather than start a new one as there's lots of useful replies here already. Combing through the quotes I've had back from the TF companies, its virtually impossible to do a like for like comparison as they all operate slightly differently. I did get a paid for quote from Estimators for a masonry build, a full turnkey quote from a Nudura ICF builder and a 'finger in the air estimate' from a local builder who's done some work for our friends and is generally well regarded in the area. A few thoughts after some detailed discussions with a number of companies more recently: The feeling is that material costs will stabilise but not necessarily drop, just the monthly increases will come to a bit of a halt. Labour prices may drop due to the pending recession and cost of living crisis. A lot of people simply can't afford to build anymore due to the skyrocketing costs, which means that companies may be forced to cut labour rates to stay afloat (I can certainly dream!) The architect's recommendation is to build in standard masonry, and he's confident that we can achieve the thermal efficiency and airtightness of modern methods of construction. Obviously harder and needs constant monitoring but certainly not impossible. Local builder that has done work for friends and is also doing some work for us currently gave us an estimate that comes in around the £2k/sq m mark (masonry build). This would be full turnkey service including demolition, foundation and all the associated works to finish the property. One thing that we can easily drop from the build is the outbuilding as the costs for that range from about £38k to £96k(!). A cheaper timber shed may have to suffice for now and we can add a more permanent structure in the future.1 point

-

As I believe the great Orlando Bloom once said "I'm just a pikey from Kent". Having to fend for myself with the whole house sick I think it's only right I take care of myself. Just finishing the evening off with a couple of corned beef and onion doorsteps and more beer followed by a packet of Shortcake (The Fruity One). Luckily I'm sleeping on my own!1 point

-

With a budget of £150 you need to do a lot yourself including design, get all your ideas down and talk to them. That budget will just get you the extension, don’t waste it trying to get an award winning architect to come up with some fantastic design, it will just get your hopes up for something you cannot afford to finish. Keep it simple, nice family area, good working space, no fancy things and you can do it. But get carried away and your budget will disappear by the time you have a shell up.1 point

-

12kWp of solar would give you a huge amount of excess, and if your DHW is instantaneous you would defo still be buying electricity even on a bright sunny day for all times where the irradiance isn’t at max / other base loads are not satisfied. With a cylinder and an immersion you could store all the excess PV generation as DHW ( plus other things ) and save a LOT of money each year as that setup would provide free DHW for prob north of 6 months of the year to both the home AND the annex. That 12kWp would diminish to sub 4kWp for the 3 months of winter, so will not even scratch the surface for space heating with resistive heaters. Used a heat pump ( which will run the split A/C, and that 4kWp will be equivalent to 12kWp again because of the CoP of the heat pump. Please ask for an explanation if you do not fully understand any of my blabbering The reason I ask about how far the annex is from the house is because it should be quite easy to tether the annex to a centralised plant in the house. My current clients want a WC and wash basin ( + DHW ) in the detached garage, so I have ducted between the house plant ( UVC location ) and the garage to run plumbing inside. I intend pulling 2x10mm pipes ( hot and hot return ) together, mummified with Armorflex neoprene insulation, to give the few sporadic handfuls of DHW p/a that the garage requires. A PIR sensor ( aka occupancy switch ) will trigger a pump which circulates DHW in a return loop to give instant DHW to the WC basin hot tap, and when the room is vacated the pipes will just cool and go cold again. The hot return will be required to stave off the “dead leg” that would be created if it was fed with just a single hot ‘leg’, but only really a requirement if the hot supply pipe run exceeds 25m ( risk of legionella ). Upsize that hot feed to a 15mm DHW supply and a 15mm hot return and feed it from the house and that’s your all of your DHW to that’s annex done for a few hundred quid of pipe and insulation. Space heating could be completely via A2A split A/C units afaic, and I would save the cost of the WBS install and use those funds to pay for the A2A system. A/C gives cooling in summer, essential for a gym(?), and space heating in the winter. The summer A/C will run from excess PV generation. The insulation levels are sub BRegs so are by no means admirable, and floating floors are cold-ventilated, so space heating in the winter wouldl benefit from the excess heat from the WBS if you do fit it as the floors will be quite a significant cold bridge during the worst of the winter, but it will likely give off too much heat for all other times, with that heat contained to the room that the WBS is in. MVHR will not distribute that heat btw. Another issue is, the chimney of the WBS will be a cold-inducing ventilation heat loss demon, which will be constantly reducing the room temps for all the times that it’s not lit. Going for a room sealed appliance would resolve this, but it sounds as though you already have a WBS? The MVHR is a bone of contention, because if you don’t get the air tightness detailed, AND tested, and get a score of <1 ACH ( air changes p/hour ) the MVHR will do next to zilch or less. Use this time and the advice available here to make some informed decisions1 point

-

1 point

-

I was responding to your thought to buy a unifi managed switch to have everything controlled under one app/console. IMO the router is far more useful and important to have control of, and useful to be integrated into the same control surface, than the switch. If you're happy to keep the virgin media hub as the firewall router then I suggest just using unifi for WiFi and nothing else, in which case just get the cheapest unmanaged PoE switch that it's compatible with the APs and be done.1 point

-

We have a Mitsubishi A2A unit in a domestic-sized office at work. Nice warm air in winter, nice cool air (if you switch it on) in summer, and well distributed throughout the office. Far superior in feel to the previous heating (night storage) heating. I cant really comment on the noise, the work environment is obviously inherently a bit noiser than a quite domestic one, but I certainly wouldn't rule out A2A on the grounds of comfort.1 point

-

It's difficult to tell whether the planners objections are reasonable without more information, however I would prepare a more detailed design and access statement disproving the planners complaints and laying out your permitted development fallback position, which by the sounds of it may be "worse" looking.1 point

-

When you're saving the planet you have to be magnanimous about things like cost. Then again, given the timescales to which I work I may break even...0 points