-

Posts

23356 -

Joined

-

Days Won

190

Everything posted by SteamyTea

-

Replacement heating for an Old Farmhouse

SteamyTea replied to Iceverge's topic in Boilers & Hot Water Tanks

TL:DR Get them to do a basic heat loss calculation. And have a look at the current bills. Without even basic data, it is hard to recommend anything really. Though A2AHPs are cheap to buy, install and run. -

Evan has been banging on about his heat pump for quite a while, even got told to stop promoting them at one stage. But now he has a show about them. https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m002sg1b

-

Batteries in plant room and 120 minute fire rated walls

SteamyTea replied to jimseng's topic in Energy Storage

They are, but the consequences are high, similar to a car fir. A tumble dryer, generally, is lower consequences i.e. less energy to burn, less spread of flame as they should be vented to outside properly. Then there is the way of extinguishing problem. 20 kWh of batteries may take a few hours. So the risk may be low, but the consequences are high. Risk management is all about the balance. -

Raft foundation - close to existing structures

SteamyTea replied to WisteriaMews's topic in Foundations

Me, @Onoff and @Pocster. Trouble is everyone else is too nice to us, so we carry on. -

ESP32 S3 m5Stack Cores3 swmbo friendly watering system!

SteamyTea replied to Pocster's topic in Boffin's Corner

The sound has just gone up two octaves. Was that the sales pitch they used to flog it. -

Matthew Syed was talking about this just today. Well worth a listen to his shows, he does not mention ping pong too much. https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m002sf4z

-

Tips on foam to stick PIR (flooring) together?

SteamyTea replied to Great_scot_selfbuild's topic in General Flooring

You can get non expanding PU adhesives. They will stick almost anything to everything. -

Batteries in plant room and 120 minute fire rated walls

SteamyTea replied to jimseng's topic in Energy Storage

I think it is quite reasonable. A lot of these batteries will be charged up over night. Teenagers don't get woken up by a fire alarm (a gentle female voice is best apparently). As @saveasteading says, 2 hours is a cheap fix, may also limit damage to the rest of the building. Look what had happened in Glasgow. Dodgy vape batteries and a major railway station is closed. -

https://www.hse.gov.uk/safetybulletins/co-wood-pellets.htm Since 2002 there have been at least nine fatalities in Europe caused by carbon monoxide poisoning following entry into wood pellet storage areas. Although there have not been any incidents so far in the UK the use of wood pellets is increasing and awareness of this danger is required

-

Only 4.5 kWh/kg. So after conversion, about 1.5 to 2 kWh. So a lot of tonnes.

-

About 10 TWh/year is turned into electricity. We use about 320 TWh/year. But I like the idea for storage. (Some of the above will be land fill gas)

-

Cold showers are what you need. ♫Rich man sweatin' in a sauna bath Poor boy scrubbin' in a tub Me, I stay gritty up to my ears Washin' in a bucket of mud♫

-

-

Thinking a bit more about it. Air pressure is what is actually doing the driving, PV/T. Change any one if them, with volume being hard to change, and properties change. This can also be affected by the Venturi effect around the building, which even in a light breeze probably has a greater effect.

-

Batteries in plant room and 120 minute fire rated walls

SteamyTea replied to jimseng's topic in Energy Storage

A bit about exothermic and endothermic reactions here. https://chem.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Physical_and_Theoretical_Chemistry_Textbook_Maps/Supplemental_Modules_(Physical_and_Theoretical_Chemistry)/Chemical_Bonding/Fundamentals_of_Chemical_Bonding/Bond_Energies -

Batteries in plant room and 120 minute fire rated walls

SteamyTea replied to jimseng's topic in Energy Storage

That is what I was questioning. I don't know the answer. -

Batteries in plant room and 120 minute fire rated walls

SteamyTea replied to jimseng's topic in Energy Storage

I don't think it needs an extra supply of oxygen as they already have the oxygen chemically bonded in the molecules. This seems to be the problem. Just a look at the chemistry shows the oxygen attached. LiFePO4, Li4Ti5O12 or LiCoO2. When working at normal temperatures, the molecules stay intact, but at elevated temperatures, some of the oxygen can break loose and react with the lithium, which releases energy. Energy is released (generally) when a molecular bond is either formed or broken. Yes, why submerging them gets the temperature down and the reactions slow. Oxygen is not the only gas that aids combustion, try fluorine, it can 'oxidise' oxygen. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oxygen_fluoride -

Batteries in plant room and 120 minute fire rated walls

SteamyTea replied to jimseng's topic in Energy Storage

I wonder how effective they are when a lithium battery fire starts. Battery fires are generally self sustaining until the fuel runs out, so getting the temperature down is the key element to tackle, a domestic sprinkler system may not deliver enough water, for long enough. Just speculating as I don't know the ins and outs of domestic sprinkler systems. We have a fire suppression system in our works kitchen. It is filled with ANSULEX Low pH Liquid Agent, what ever that is. Sounds like a treatment for piles. -

The 'glazing' is multi wall poly carbonate sheets, they go 'milky' after a short time and look dreadful. Do they offer an acrylic option ?

-

Batteries in plant room and 120 minute fire rated walls

SteamyTea replied to jimseng's topic in Energy Storage

BSI PAS are technical specifications and not laws, or even minimum standards. While I am not saying they should be ignored, and may even be specified within laws, it would be so much easier if Building Act was available to the public free of charge. Though a quick web search did throw up this. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1984/55/data.pdf https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1986/44/contents https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1989/15/contents https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2022/30/contents So maybe government is getting a bit more open. -

Electricity tariffs

SteamyTea replied to Russell griffiths's topic in General Self Build & DIY Discussion

Octopus has just put a £75 exit fee in place on new policies. https://moneytothemasses.com/news/octopus-energy-announces-new-exit-fees-due-to-volatile-market -

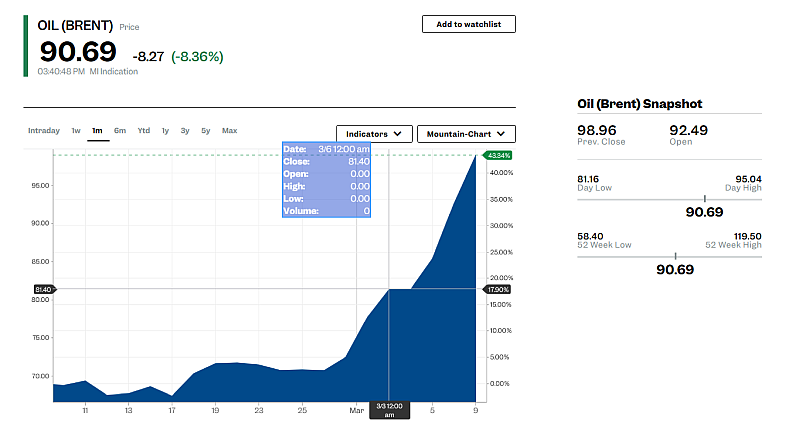

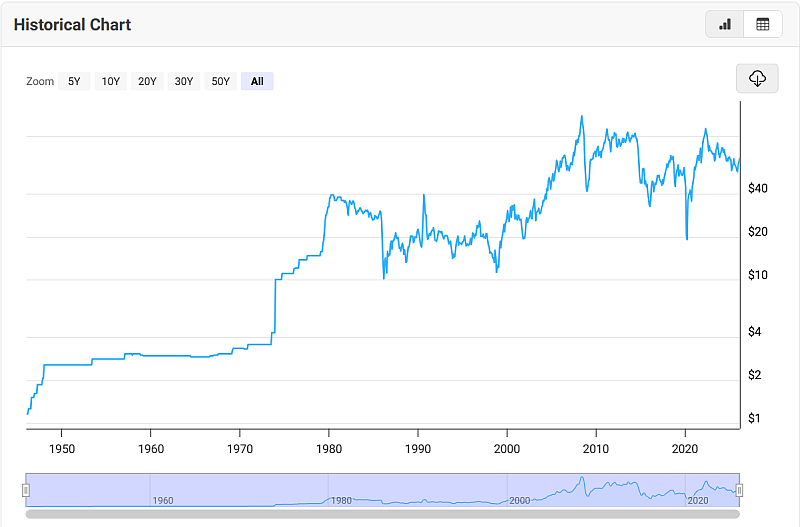

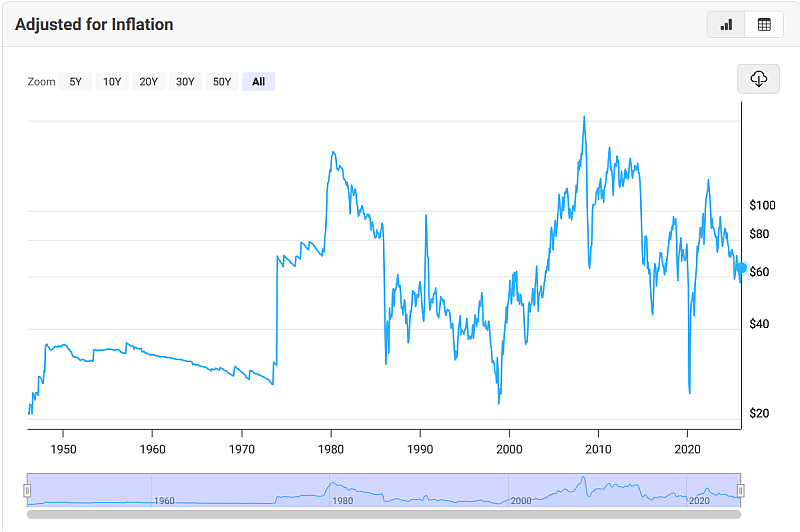

You have not seen the price of cod recently, we stopped selling it a while back. Now this is oil prices, let us see how far the go and for how long. Data is up to March 1st Two charts, nominal price and inflation adjusted for WTI crude. Data from here